Imagining ceremonial instruments of Lemuria

Lemuria is the name of a parallel, mythic, subaquatic place and culture located in the western Indian Ocean. It is based on the idea of a sunken land first imagined by European naturalists in the 19th century seeking to explain similarities in fossils across the indian Ocean islands and the Indian Subcontinent, but has since been reclaimed and adapted within Afrofuturist and Afro-surreal realms by artists like Sun-Ra, Drexciya and Abdul Qadim Haqq. Inspired by traditional instruments of Sega, Moutya and Maloya – musical styles of the region.

The central instrument of Sega and Moutya is the large circular frame drum. It is a symbol of Creole identity and resistance, having survived bans and repression since it was developed on the islands during slavery. The drum, known as a Ravanne in Mauritius and a Tambour Moutya in Seychelles amalgamates memory of frame drums from Africa, Madagascar, Asia and Europe.

On the small and distant outer islands of Seychelles and Chagos the drum was made from skin of sting ray or shark. The shape references the moon, source of the ocean’s knowledge. The centre of the drum is called the fon (the deep) and the edge is the lezel (the word for both wings and fins in Creole). The kelkel (underarm) is the part of the body the drum covers and hides, but the drum also allows the player to speak hidden truths directly from the kelkel.

In origin stories carried by ancestors from western Madagascar, the kelkel was a secret and taboo part of the body that should not be shown or mentioned. It was the part of the body, on the first ancestor who came from the sea and began a new lineage on the land, that contained those things that fish use to breathe – g***s (it was also forbidden to speak that word). The drum has been coralised and further creolised in the ocean.

The triangle was absorbed into all of the traditional music styles of the western Indian Ocean islands much more recently, to provide an emphasis to the rhythm that cuts through the rest of the music.

Papa Fransen

In Seychelles Creole ‘Fransen’ (or also Fansen) is a type of bird known for perching on small floating objects far out at sea. It was the nickname of my great-grandfather who was known for having left the small island of La Digue in a tiny rowboat, crossing a dangerous stretch of water that his own grandfather had drowned in, to reach the main island of Mahé. It was there that he met my great grandmother and began a family.

His sea crossing is remembered as a family origin story. I drew him from one of the only pictures that exists of him, in chalks found on Margate beach and charcoal, on an oar that used to belong to my father and grandfather before that. I don’t know if it is the oar of the crossing or not, but I choose to imagine so.

Seni

These woven baskets were traditionally used in the Indian Ocean Creole islands for sorting rice, spices or other cooking ingredients, salting fish, and carrying or displaying objects for sale. They were also used in ‘gri-gri’ (an Indian Ocean Creole practice of spirituality, magic, herbalism and divination) to hold ingredients used in spells and as a surface for casting shells, bone, seeds, coral, stone, dominos, cards and other objects used in divination. This one belonged to my great grandmother who worked as a fortune-teller. It was brought with my family when they migrated to the UK before I was born. When I grew up it was on the wall in my grandparents’ house, like a circular porthole to the past. I inherited it when when my grandparents passed away. I drew in it this portrait of my great-grandmother, mostly from memory, with charcoal and chalks from Margate beach.

Shell man

Antoine Manes was known to many as the ‘Shellman of Seychelles’ – until his death in 2024 he dived for, and collected, rare and beautiful sea shells. He was known for having the best collection on the islands, for having discovered now types of shell and for selling shells from his shop in Victoria. He was visited by shell enthusiasts from all over the world. His passion always moved me and I’d always look forward to going down to his shop to see his new finds and have conversations, about his life, the sea, and what shells meant to him. Finding out of his passing moved me to draw him, on a shell of course, and adopt him as an ancestor I’ll continue to honour. To the friends and loved ones I’ve given cowries to before about 2024 – especially if they were shiny, they likely came from Antoine.

From The Ship

The middle row of photographs shows three ancestors from the 19th century who arrived in the islands through different ship routes, as well as wording from surviving documentation about them.

Antrasiah was an indentured southern Indian contract labourer who was recruited by the British to work the island sugar cane fields.

‘Hilorie’ (real name unknown) was a 14 year old Makua girl who was trafficked by Arab traders and recaptured by the British anti-slaving squadron. They delivered her to the Seychelles where she became a forced plantation labourer.

Alfred Strous was an American whaler who deserted, by swimming, while his ship was anchored off the Seychelles.

They represent the Asian, African and European elements of the Indian Ocean Creole identity. The images surrounding them represent the merging of the three groups and conversion into memory in later generations.

History, Memory and Imagination in Conversation

Part of the Thames Estuary Sunken Slave Ships R&D exhibition at Crate Gallery Margate.

Film by James Jordan Johnson, sculptures by Christiana Peake and installation by myself, Victoria Barrow-Willams and Margate community members.

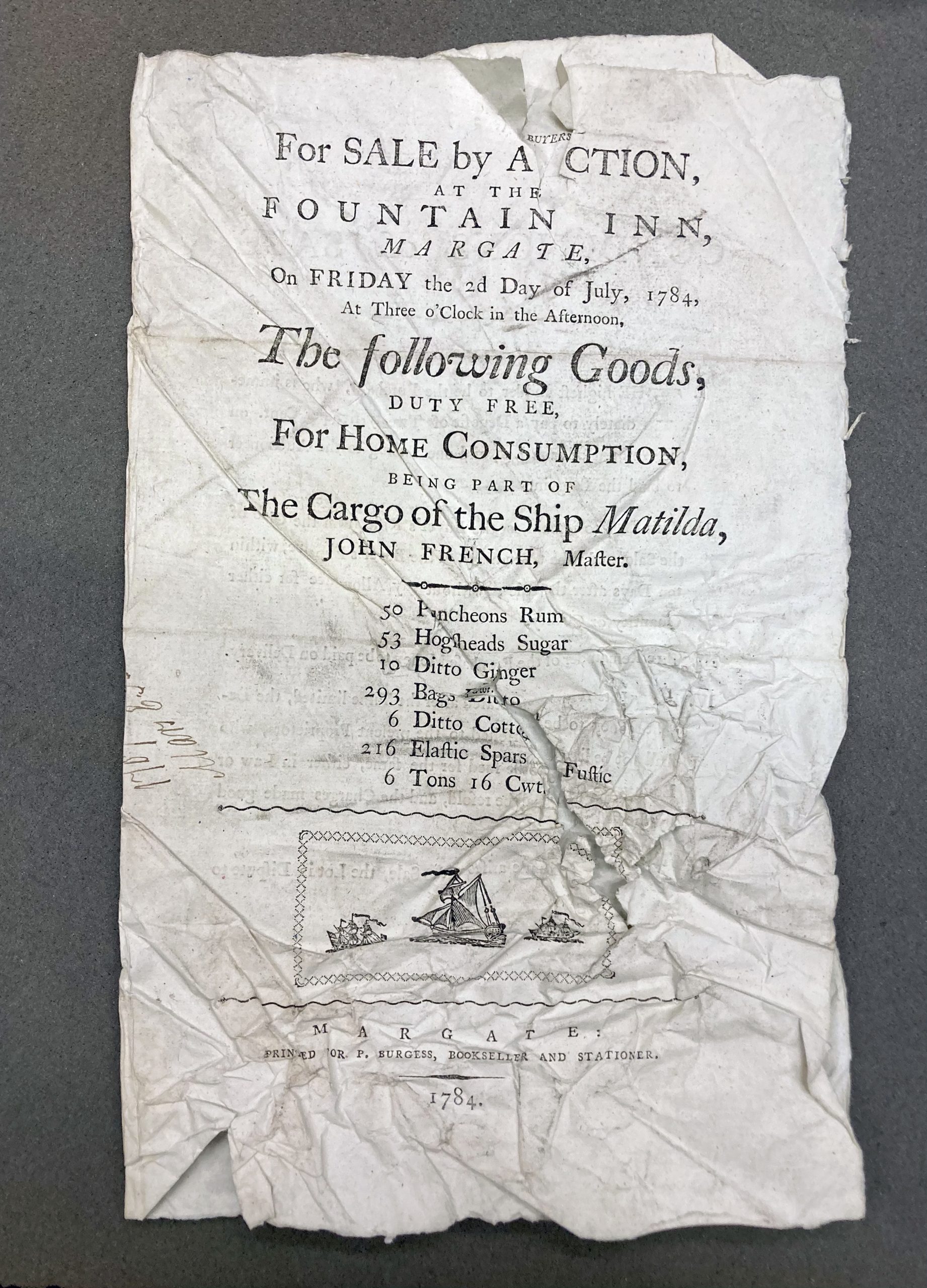

Exhibited alongside enlarged documents found during my research in the Kent Archives advertising an auction of salvaged wet goods made by enslaved people in Jamaica, spilled into the sea during the wreck of the Matilda in Margate in 1784.

Shell Archive

Collaboration with Victoria Barrow-Williams of People Dem Collective and Margate Community Members

These shells belong to people in Margate of various Caribbean, African and Creole origins. They have been collected or inherited over lifetimes or generations.

Some were collected in Margate, some have travelled with us, or our elders, as links to places of origin. Here they have been ‘archived’ as objects that carry history and memory, transmitting textures, colours, sounds and stories of the ocean that shaped our pasts.

The shell that I contributed to this was found by my grandfather in the Seychelles and brought to the Kent coast when my family moved here in the 1970s. My grandparents at that time collected items and displayed them in a cabinet like the one used here, it was still in their house when I grew up in the 1990s and 2000s. I remember looking inside it to see things they’d brought with them on a journey through several countries to arrive in the UK, items sent by friends and relatives, souvenirs of London and the Isle of Wight and even Happy Meal toys ended up in there. It was one of the ways that we ‘archived’ our family history.

(Marine Salvage) Divination Set

Collaboration with Christina Peake

To develop this piece Christina and I had several discussions about the findings from my research on the Thames Estuary sunken slave ships. Within the research, Christina was especially moved by stories of mothers trying to protect their children in the hold, and the discovery of a collection of bones from the only existing excavated wreck in the North Sea. It’s thought that these bones might have been part of a talisman and we discussed the idea that they could have been smuggled onto the ship by an enslaved mother as an object of protection for her children.

The sculpture Christina created responds to ideas of multiple cultures and cosmologies being compounded, and the retention of knowledge, culture and ecologies as forms of protection and resistance. Christina imagined a salvaged divination set from the hold as something used by a new community striving to enable a single child to survive. The divination set is something that is passed around, with each person guarding a piece. Every evening the pieces are used to recount histories to the child who absorbs the knowledge held in all of them. Each piece has a different function – to map a place, to carry seeds or to reference a water deity.

Pamphlet for auction of goods made by enslaved people from St. Croix

Document found in the during my research at the Kent Archives, curated for Margate exhibition 2022.

A pamphlet for auction of goods made by enslaved people from St. Croix, salvaged from the wreck of the Prince Frederic in Margate 1782.

Displayed upside down to follow the train of additions made as the pamphlet is used as scrap paper during the auction.

Coralised Vessel

Vessel found in the Indian Ocean, encrusted in coral.

‘A Song from Below’ is a soundwork honouring, and reaching out to the more than 500 people trafficked aboard the Henrietta Marie – a slave ship that was fitted out in the nearby town of Deal and passed through our Thames Estuary waters more than 300 years ago. It is created from the sub-audible frequencies in the resonance of the ship’s bell, forged here and pulled up from the seabed 300 years later, off the coast of Florida. The sub-edible frequencies have been brought into our hearing range to represent those histories, voices and souls that lie beyond our reach, and the Creole traditions of breaking, rebuilding, ‘bastardising’ and subverting colonial materials to reach our own truths. Community members were invited to converse with the spirit sounds from below using traditional Creole instruments. The work was played over the water on loop at the very end of the Ramsgate harbour arm, overlooking the ship’s route, as part of the Ramsgate Festival of Sound 2024. Find out more about this work here.