‘A Song from Below’ is a soundwork honouring, and reaching out to the more than 500 people trafficked aboard the Henrietta Marie – a slave ship that was fitted out in the nearby town of Deal and passed through our Thames Estuary waters more than 300 years ago. It was played over the water on loop at the very end of the Ramsgate harbour arm, overlooking the ship’s route, as part of the Ramsgate Festival of Sound 2024.

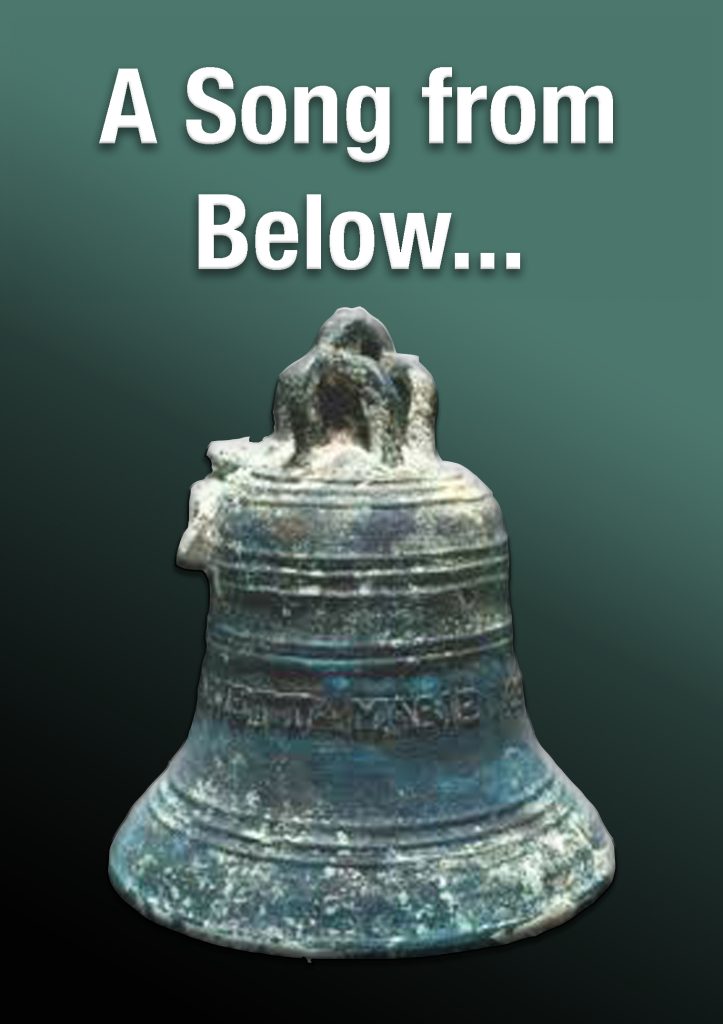

What I’ve tried to do is bring up hidden sounds that vibrate on frequencies below the normal range of human hearing, taken from deep within the resonance of the time-keeping bell that was recovered from the sunken ship when it was found off the coast of Florida in 1983. The sound of the bell, which was heard continuously as captives were carried over the ocean and into the saltwater realm was recorded and archived by the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum in Florida, USA.

When marine archeologists, working on the then unidentified wreck off the coast of Florida, discovered the 14 inch brass bell and scraped away the centuries of accumulated coral, the inscription of the ship’s name and the date, 1699, revealed the wreck to be that of the London-based slave ship. That, as well as markings on several iron cannon showed that the ship had been fitted out in the port of Deal with these metal works forged in Kent and Sussex.

The bell was used to keep time, order and control over the ship and was struck every 30 minutes when a sand timer emptied. When the ship left London and passed Ramsgate, the sound was carried across the water directly in front of us. It was eventually carried into the estuary of the Rio Real, to the town of New Calabar in modern-day Nigeria and other ports in western Africa where more than 500 captive people were carried away on two separate voyages to British plantation colonies on the other side of the Atlantic.

None of the people who were trafficked on board the Henrietta Marie are known by name, and no stories of them survive in any written record. Documents only offer cold estimates of numbers of adults and children bought and sold, or numbers of those who died on board and were thrown into the ocean. Everything else about these ancestors has to be reached through what the Martinican-Creole poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant called the ‘blue savanna of memory and imagination’ – the last metamorphosis of an abyssal state of history and being which began with the birth of new realities forged inside the ‘womb’ of the ship before it delivered saltwater captives (the colonial term for fresh arrivals) and their Creole descendants into a ‘non-world’.

Below decks and below the water line, the ring of the bell every 30 munites, along with the sound of the ocean’s swells were constants during the three month crossings. These same waves of sound and water reach through time and space into here and now, through an abyss and through realms of materiality and spirit. Eroded and corroded, coralised and creolised, broken up, rebuilt and reimagined, the hidden sounds in the resonance of the shipwrecked bell function like the Creole languages and music styles developed by ancestors beneath the surface, illegally, and in the cracks of systems that allowed them no space to exist. They function as energies with the potential to build connection where none was to be allowed, to counter spiritual crimes, and repair damage caused by the severing of links between ancestors and descendants.

In Creole tradition this severing, silencing, and spiritual harm is resisted by co-opting, re-imagining, re-threading and re-purposing the infrastructures and symbols of the eroding forces. Traces of ancestral spirits are acknowledged as hidden dualities of the imposed christian saints; African, Asian and Indigenous American or Pacific words and grammar structures forged with broken up French, English, Dutch, Spanish or Portuguese led to the building of Creole languages that could speak of experiences in tongues native to the saltwater realm; when African drums were banned and burned, the European tambours were taken and stretched to accommodate the forbidden rhythms of ancestral connection. In the hidden frequencies of the metallic ring of this bell is the call of Ogun, sovereign of iron, forger of metal, spirit of strength and resistance, remembered in different manifestations throughout the diaspora and carried illegally by those who refused to allow the erasure. In the Seychelles, the ancestral figure of resistance, Pompée, used the forged iron field tools he was forced to work with as weapons to strike down the masters.

The sounds from beyond our normal hearing capacity are reminders of the possibilities of extending our range of perception when thinking about the past, in a way inspired by Labelen – the Creole spirit of memory who is imagined as a whale spirit able to hear well into these frequencies and the other sounds of the deep. She can also sing back what she hears on the seabed, sending and receiving messages from Anba Delo – the underwater spirit world that displaced souls return to, or through. Like the Creole languages and music styles that developed alongside the constant ringing during the crossings, the hidden tones in the bell are sonic channels of connection to the millions of lives, names, experiences and histories that exist out of reach and out of range, accessible only through imagining from beneath the surface.

To mark 4 days of the sound playing on loop into the sea, we celebrated ancestors in the water with offerings and music.